Investing for Good - Why is it So Hard?Investing for good. Those three words summarize an incredible diversity of investment approaches and asset classes. Everything from fossil fuel divestment to impact investing to religious screening to green bonds fall into this camp. Although there are plenty of investment styles that attempt to “invest for good,” ESG seems to be getting most of the assets (or at least, most of the press). Environmental, Social, and Governance – these are the ingredients of ESG. We’ll use so-called “ESG” investing as our example of investing for good throughout this paper as we grapple with some of its most thorny problems. Both institutions and Main Street investors are expressing a desire to make an impact with investments, and Main Street investors are directly applying pressure to institutions across the country to make big changes with their big dollars. Sustainable investments have now reached $4 trillion, according to Larry Fink of BlackRock’s latest annual letter to CEOs. Investing for good can’t be ignored. Unfortunately, it’s also a lot harder than it sounds to execute successfully. Working with both Main Street investors and institutions, we’ve seen a number of common misunderstandings pop up when investors try to understand, evaluate, and implement “do good” investing. Today, we’ll take a closer look at some of those misunderstandings and bring to light the most pressing issues that come up when our clients try to tackle do-good investing. The three thorny problems we address in this paper are:

Thorny Problem #1: The Big Tent  The easiest way for an investor of any size to get started with ESG is to buy one of the many passive index funds available today. These funds are cheap, easy, and accessible. But do they offer what investors want? I wonder if anyone has studied the proportion of ESG investors who care about all three letters: E (Environmental), S (Social) and G (Governance). Even within each of the three pillars of ESG, these are big groups that try to tie together the values of many disparate individuals. Let’s dig into S(ocial) as an example. If you think about the early days of ESG investing, the original S(ocial) investment fund often followed religious principles. In many ways, the original S is a relatively easy problem to solve as a fund company since the religion itself has a stated, defined belief system that large populations of individuals follow. Prominent religious figures provide guidance to the fund company in accordance with that belief system, and a fund is born. The market has exploded today, and values systems that fall under S(ocial) have multiplied. For some investors, S is still screening based on religious principles. For others, it’s about Societal benefit – including rewarding companies with forward-thinking employee benefits like family leave. For still others, it can be gender equality or diversity or any other number of deeply rooted social issues. Which S is which? Multiply that by varying possible interpretations of E(nvironment) and G(overnance), and you start to see the issue. Trying to solve the Big Tent is how you end up with a fund excluding companies that:

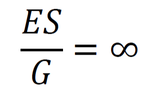

So – raise your hand if this entire list aligns with your belief system. … Bueller? Most likely, your answer is “no.” You might want to divest from fossil fuels but have nothing against alcohol companies, for example. This is the Big Tent problem in a nutshell. ESG investing is a blunt tool, and it’s unlikely to truly reflect the value systems of most, or even many, of the investors it attracts. Institutions have an even larger problem. Why? Because an institution may have an overriding mission statement that drives its vision, but institutions are also comprised of lots and lots of individuals who bring their own ideas, biases, and visions to the table. For example, student activism on college campuses aims to drive change in school endowment portfolios. A popular aim of student activism is to seek divestment from fossil fuels. Does this align with the mission statement of a school like Harvard University? Maybe – it depends on who you ask. Divest Harvard certainly thinks so. It is especially important for institutions to be mindful of the Big Tent problem in order to effectively work through conversations around ESG and other related investment styles. Who, what, when, where, how, and why are key questions to come to consensus around before implementing an ESG-style portfolio to ensure that the investment approach truly aligns with the mission of an organization. Let’s say your organization has undergone a thoughtful, deliberate process to consider ESG. Your consensus is to start incorporating ESG into your portfolio by buying a broad-based ESG index fund. Great start! Your constituents are thrilled. Or are they? That brings us to another thorny problem which I like to call The Swoosh. Thorny Problem #2: The Swoosh  I own WHAT? Once you adopt ESG as an organization, you’d like to think that investor outrage over your investment holdings subsides. After all, you’ve gone through a process to develop an ESG approach and align the portfolio with that approach, so everyone should be happy now. Right? Not so fast. One of my most memorable ESG fund due diligence calls was when a manager told me with a straight face that [a certain producer of athletic shoes] was a major holding in that fund. You mean the one with all those 1990s sweat shops? Yes, that one. The company made the grade in this particular portfolio because they scored highly on the governance “improvement” metric. In other words, they started from a very low hurdle and managed to clear it. Welcome to the hallowed halls of ESG. Investors who want ESG in theory might not understand the compromises that building an ESG portfolio entails in practice. As we saw in the past example, ESG funds cast a wide net and own plenty of “ESG in practice but not in spirit” companies. Maybe what those constituents really meant was that they want you to own forward-looking companies investing in technologies that may save the planet — for example, electric cars or clean energy—rather than owning stocks that score highly on a confusing matrix that intersects E, S, and G without really focusing on investing to do good. Some large investors have the option of impact-oriented funds who seek out and fund such niche projects, especially within private assets, but those types of funds are not available to all. Niche public equity funds exist, but they tend to suffer from The Swoosh. Take a look at a “clean energy” mutual fund, for example, and you’re sure to see a lot of major utility companies. Why? Because those companies are funding clean energy like wind and solar as a division of the larger company, not as a standalone investment. Another example is the automotive industry, where major producers of gas guzzling vehicles like Volkswagen are also developing and building electric cars. You have to buy the past to buy the future. You don’t want to own the past? That brings us to our third and final thorny problem, The Fraction. Thorny Problem #3: The Fraction No, not that kind of fraction. This thorny problem starts with the realization that off-the-shelf ESG options don’t meet an institution or individual’s needs. “Let’s just design a custom portfolio that meets our investment objectives AND the ESG principles we’ve agreed to,” you might think. Great idea! But not so fast. Main Street investors and small institutions face the problem of fractional shares — most small portfolios simply don’t have enough dollars to invest in truly customized portfolios without buying less than one share of many stocks. If you have $10 to allocate to Apple, but a share of Apple costs $200, you must have the ability to buy less than one share (a fractional share) in order to build your portfolio. This technology is slowly making its way to the market, at least for US equities, but it is currently very limited. Fractional share investing works in concert with direct indexing to enable small portfolios to build customized ESG portfolios. Direct indexing allows an investor to start with a public index (like the S&P 500) and strip out anything that investor does not want to own. Don’t like Volkswagen? No problem, just exclude it from the index. Larger institutions have some direct indexing options available (like Aperio or Parametric), and our hope is that these options become more available to smaller investors as technology improves. Larger institutions have a separate but related fraction problem, where the portfolio itself is invested across many different asset classes. Investment dollars in any one asset class is a fraction of the whole (potentially leading these institutions to face the same fractional share problem as smaller investors), and there’s the added hurdle of whether customized ESG can reasonably be implemented in some asset classes at all. Spoiler alert— it probably can’t. US stocks are the easiest asset class in which to build customized ESG portfolios (and the larger the market capitalization of the stock, the easier it is). Logistical hurdles to implementing custom ESG portfolios multiply outside of US stocks. Data availability can be spotty in international markets, and countries may vary in their investor registration requirements. Bonds are even more complicated. Each share of Apple stock is the same, but each Apple bond issue is unique, so supply is very constrained and make individual bonds hard to purchase in small lots. There isn’t a lot of ESG-friendly bond issuance to choose from, either. And then there are alternative asset classes like private equity. Private investments have a whole host of challenges that institutions must grapple with, like access and illiquidity. Investors may not be able to access private funds that align with their values at all, or they may not be able to withdraw from a fund who later makes an investment counter to the investor’s ESG guidelines due to the illiquid nature of these investments. In each asset class, investors must consider the availability of ESG options and compromise, compromise, compromise. The Compromise There are very thorny problems with ESG, whether you have $100 or $1B to invest. Committing to ESG or other do-good investing requires compromises every step of the way. A strong understanding of what’s possible to achieve in your portfolio with the tools available to you today is critical to success for any investor. If you’re starting down this path as an institution, we can’t stress enough how important it is to educate, educate, educate, and to take the time to build consensus with your constituents around a meaningful, aligned ESG approach. Yes there are thorny problems, but this is a worthwhile endeavor to consider. With $4T invested in sustainable investments already, and more added every day, these conversations are only becoming more important. We hope that this paper has helped you start thinking of ways to overcome these challenges.

Want to share this piece? Download the paper here. Comments are closed.

|

Author

Anna Tabke, CFA, CAIA Interest

All

Archives

April 2022

|

Copyright © Alpha Capital Management